Tuesday, 5th May 1925

Tram number 21 was chugging slowly towards the Wysockiego terminus. Andrzej Zaleski was one of the last passengers. Those few, travelling at that time of the day, got out near the railway workshops. Now in the car remained only an old auntie, going most likely to one of the small Ustronie cottages, and an ancient conductor.

The morning post had brought a short note from Michał. “Please do come to my school. I have encountered a very strange problem, the type that requires your skills. I won’t manage myself. Yours, Michał”.

His relationships with Michał – his foster son, were a bit tense. Michał’s parents, farmers from his home village Białaczów, had passed away during the 1892 cholera epidemic. Zaleski formally adopted his father’s godson. Even before, following his father’s last will, Zaleski brought the boy to Warsaw and took care of his education. Michał completed studies at the reputable Warsaw-Vienna Railway School, and demonstrating strong technical abilities, went to the Petersburg Technical University. As a freshman engineer, he worked in Belgium, at that time the best place to learn the trade. World war, and later the Bolshevik’s revolution made their contact impossible for almost five years. In the independent Poland they drifted apart.

Andrzej struggled to adapt. At the start, like everyone, he was brimming with enthusiasm. In 1920, during the Polish-Bolshevik’s war, he commanded an armoured train, collected a good throng of fighters on Russian and Ukrainian steppes and managed to break through the front to Kiev. He was made a battalion commander, but was quickly pushed aside. Russian socialists were not trusted in the Legions and Hallers’ army. The generals remembered the Socialist-Revolutionaries red-green flag[1] he sported from the train engine, when it entered the Kiev station.

Of course after the war he re-joined the police force. It was his destiny. He loved working at the police and was a very good detective indeed.

However, it quickly turned out that those who once had served in the Russian Imperial police were not really welcomed . He was given a Chief Inspector post in a financial crime investigations department, a good two ranks lower than his pre-war rank of Chief Superintendent. Nothing to compare with the full colonel he attained at war. He didn’t mind the rank, but he hated pushing papers. He missed fighting the real criminals, investigating the underworld. But then they sidelined him further – to the river police. He supervised autopsies, documented drownings and was clearly kept away from any important duty. So, one year ago, when his arm, damaged in an 1890 police action, got worse, he jumped at the retirement opportunity. He was given a nice handshake, they even awarded him the Virtuti Militari[2] cross for getting the armoured train to Kiev and then forgot him immediately.

To the contrary, Michał was thriving in the new reality like a fish in a pond. He was building and rebuilding railway infrastructure, heavily damaged during the Great War. His engineering projects made headlines. He was photographed with both ZLN[3] politicians and Piłusdski’s ex-socialist legionnaires. A year ago he had become the new railway school headmaster.[4]

Andrzej and Michał disagreed on many topics. They argued about abandoned land reform, lack of social justice, treatment of people coming from different pre-war partition[5] zones. Michał believed that the first state obligation was to rebuild the country after war damages. Fronts had passed through Poland four, and in some places six times. Industry, transport and even agriculture were in shatters. Therefore, the economy should come first. The time to take care of the poor, who were in fact 80% of the society, who suffered from hyperinflation and who had fallen victims to the recent monetary reform[6], would come. Later. Much later.

Andrzej stayed true to his socialist ideas. He believed that one cannot build a strong, modern country on poverty and social injustice. Even if, after the Russian revolution experience, he kept clear of the communists.

As a result, they were neither seeing each other often nor talking much. Andrzej spent time at his apartment in Ząbkowska, alone with his wife Anisa and two cats. Bored to death. Feeling lonely and useless. So, the son’s letter brought him joy and some bitterness too. They need him. That’s good news. But Michał remembers him only when he can’t cope by himself. Andrzej tried to steer away from any police matters. We have the state, the administration, the police are there to keep the law and order. Civilians should mind their business. Obey the rules.

Anyway, Zaleski didn’t waste any time and jumped aboard Tram 21, which recently linked Bródno with the city, and by now the car was slowly approaching the end stop. Wysockiego street was empty and silent, a big contrast to the busy railway workshops at Białołęcka street. The spring day was cool, grey and wet. Cobbles were shining from recent rain and the traction reflected in large puddles. He pulled his hat tighter and shivering from the cold wind went towards the school and the dorm. The building was glimmering behind the trees with new tiles and shiny metal parapets.

The old school caretaker recognised him immediately.

Pilsudski moustache on a coin

– Good morning chief inspector, have you come to see the director?

– Good morning Wojciech. I am not a chief inspector anymore. Plain old pensioner, same as you. – Andrzej whisked away the drops that collected on his moustache. He sported a popular Piłsudski-like look. Already in 1916 he had shaved away the old Imperial-style sideburns.

Zaleski climbed the stairs.

– Good morning chief inspector. – The old spinister who guarded Michał’s office and kept the school administration running, offered a sad smile. Her eyes, behind thick glasses, were red and swollen.

– Good morning miss Janina. You look stunning in that new hairstyle. Pity I am married already.

– And mister inspector is full of jokes, as always. – Her smile beamed more genuine and even her cheeks got a little rosy. – The Director’s waiting.

Andrzej entered the spacious, contemporary outfitted room. Black wood, chrome, glass. The railway school is the symbol of country modernisation and should look correspondingly. Large maps and charts showed rail reconstruction progress. In recent years the state made a tremendous effort to build connections between old partitions, erase the borders, reconstruct bombed bridges, destroyed stations, and bring some sense of progress to the poor east and south.

– Morning father – Michał jumped from behind his desk and shook Zaleski’s hand.

– Morning Michał. How come you recalled that you still have an old father?

– No need to be bitter. You know how it is at work. As you said during the old regime: “No time to wipe your…”. The rebuilding is going at full steam and the school consumes whatever time is left. We need a new breed of technicians badly, yesterday if possible. And now those thefts, I don’t like it.

– Maybe we start at the beginning. – Andrzej smiled, sat down, and took a cup of strong tea from Janina, nodding graciously.

Michał waited for the doors to close before he continued.

– For some months we at school have suffered a plague of small thefts. Gold necklaces, rings, lockets, cash. We have not caught anyone. It is becoming tedious. Can you imagine, the losses have mounted up to 500 złoty[7]?

Zaleski whistled.

– Five hundred. Good chunk of money.

– Exactly. And recently someone nicked a gold bracelet straight from miss Janina’s wrist. Antique piece of jewellery, family heirloom. Miss Janina can’t stop crying. She just can’t believe that such thing happened here, in the very school. That is serious.

– What do the police say? Surely that warrants police attention.

– You know father. Our school sits like on a fence. Formally we are under XVIII Railway Police Inspectorate, and they are interested in “goods, rail stock, signals, passenger safety”. They just don’t care about our affairs. And the local force from the XXV Precinct didn’t even want to talk. They are busy chasing communists. They have become very active, here in Annopol among the poor and in the factories. Can you imagine that communist propaganda becomes popular even among rail workers? You should also understand that Bródno is not exactly a peaceful place. Crime is abundant. Every day one can find someone mugged or with throat cut. Those thefts are too petty for the police to bother. As for myself – first, I just don’t have time…

– And second, you hate detective work. That I remember very well. – Andrzej smiled recalling how he tried to drag Michał into helping him in solving crimes. Failed miserably. – OK, please tell me everything in detail, step by step, like a good engineer.

– It all started four months ago. Antek, preparing for Technical University exams, lost a golden cross. A large one. Gift from his godfather. Same week 10 złoty vanished from an Eight Form guy and the a Ninth Form student’s gold ring, taken off just for a bath, evaporated. Ever since we have two, three small thefts a week. All very clever. Golden locket disappears after gym classes. Two złoty coin missing from the pocket. We announced that gold and jewellery should be deposited. The very next week two gold necklaces went missing from the safe box.

– Have they stolen everything from the deposit?

– No, silver and watches left intact. Quite bewildering. But when miss Janina’s gold bracelet was nicked, I decided to call for your help. Maybe you have retired, but surely you will welcome a small brain exercise.

Andrzej winced. He didn’t like when people remind him of his retirement. Even more, he hated when any investigation was taken lightly. During his police work, he learned that even a small crime can lead to a fatal outcome. He remembered the tragedy just outside Kiev. An angry village crowd beaten a half-wit to death, for pilfering two eggs, and that was well before war hunger times. From his experience, so-called justice, administered by youngsters among themselves, could be as cruel. Those thefts clearly required attention.

He cleared his throat.

– Well, I will talk with the boys. And, of course, with miss Janina. In two-three days I should get wind of what’s going on. By the way, give me a monthly pass to the railway workshops. Tell them that I will nose around. I feel there may be a connection there.

In fact, he doubted that the workshops could be connected in any way, but he wouldn’t miss the chance to visit them. To sit again among the rail workers, inhale the smell of the grease, hammered metal, fire. He would not deny himself the pleasure of inspecting rail stock, of seeing the big steam engines at close. As a true XIX century child he admired railways and the industry. Steam, electricity, progress. Thanks to the railway men he once resolved one of the most important crimes in his life. Then he rode the armoured train from the Bolsheviks’ Russia, back to Poland, to freedom. Who knows if now would not be the last chance for an old pensioner to encounter the true industry?

Friday, 8th May 1925

For the next days Andrzej wandered seemingly aimlessly through the school and the workshops. He chatted with students, teachers, janitors, workshop workers and instructors. Played an innocent old man, who can be trusted and is completely harmless. With older boys he smoked a secret fag, young ones he asked about home and mollified their homesickness. He sat near machines enquiring about workers jobs, admired their milling, lathing, and casting skills. Gossiped over tea with teachers. With old caretakers he took a quiet sip from his hipflask. No rush. Always took notes only after the conversation. He knew that when people see you writing they bottle up. Also scribbling distracted him from the real substance.

– How is it going? I can see that this “small thing” from Michał really got you – asked his wife Anisa when he got home later than usual. The trams had stopped already so he had to take a horse cab. – You are working yourself up. Be careful.

– I am not as old as you think. – He replied smiling. Sitting in his comfortable armchair he petted his favourite Morus. The black, silky cat took the opportunity of his return to reclaim his place on Andrzej’s lap. – I will manage. At first, I thought about cards. You know, students play with local swindlers, lose and steal to repay debt. However, that is inconsistent with the stolen goods. A gambler will not pass silver or a good watch. Here they took only gold or money.

Anisa smiled, stroked his hair lovingly and placed a plate full of small hot roasted Tatar pierogi he loved on the small table. She knew that while working he preferred to nibble something and would not want to stop for dinner. He just sat there in the armchair, in the golden circle of light, petted the cat and from time to time scribbled a note. Well into the small hours.

Saturday, 9th May 1925

A. Kupniewski drawing, 1940 – Tram 21 Terminus, school top right

The next morning, Zaleski mixed with the early crowd on Ząbkowska street. Jews leaving kosher butchers, house servants carrying full baskets from Różycki market, factory workers rushing towards Kawęczyńska street or business travellers hurrying between the rail stations. Heavily loaded horse wagons bumped noisily on the cobbled street. The smell of fried onions mixed with freshly baked bread, human sweat, and horse piss odour. Near the Wileński station the crowd didn’t thin at all, and when the “twenyone” approached, Andrzej was forced to hang on steps outside. The tram was packed with factory workers, smelling of grease and tobacco, or the soap from the new Schicht chemical works[8]. A few railway men in their immaculate black uniforms turned noses up. They felt above average blue collars. True elite. Safe, state job. Nothing to worry about. At the Konopacka and Szwedzka street stops the crowd thinned, and when the tarmac Odrowąża turned into cobbled Białołęcka street the tram was practically empty.

Michał waited, tramping around nervously.

– What do you know father? Have you discovered anything?

– The “what” is pretty obvious, I still don’t know who and why.

– What is so obvious?

– The modus operandi[9]. You have two or three very clever pickpockets among your students. They operate in the classic way. When people mill around one distracts the victim, the other one steals. Or when the boys are busy with something else. Someone here has really nifty fingers.

Just listen to miss Janina’s story. “Students were joining the morning roll quite orderly, class by class, headed by teachers. All of a sudden, the little John from seventh form stumbled and people jammed in the hall doors. Older boys pushed forward, young ones started to scream. I run forward to help; it didn’t take long at all. During the Director’s speech I felt something was amiss. Then leaving the assembly hall I noticed that my bracelet’s missing. You need to understand chief inspector, we kept it in the family since the Napoleonic wars. My great grandfather brought it for his bride from Spain”. She started crying.

In my opinion they act on the spur of the moment. Occasio facit furem[10].

– No, please. That’s really horrible. Pickpockets in the railway school! One day students would become service men and then what? Will they rob the passengers? No way. We cannot let them prosper. Please father, catch them.

– Tell me, who from your boys can be trusted?

– The students? Edek Popławski and Julek Mazur are boy scout leaders. I trust them completely. Also, I think Antek Poświatowski is clear. He comes from a noble family, they send him cash regularly, why would he steal? Antek started to work in the workshops, earns money there, very capable guy. And he was the first victim. Certainly, beyond suspicion. As for the others, you need to ask teachers.

– Are you ready to part with a few quid to catch the thieves?

– How much? – Michał was not exactly a keen spender.

– Two local guys, you pay a score each, when they do the job. Kind of evening shift.

– Score each, totals forty, OK. Do you know someone here?

– I would have been a very poor policeman indeed if I didn’t have my contacts in Bródno. I know some smart guys. They used to work in the metal factory on Szmulowizna, but after new taxes last year the workshop closed down. The dole dried up quickly and now they are in need. They wouldn’t help the police, but for me they can do the job. Now, can I talk with Edek and Julek?

– With Antek too?

– I will stick to the scouts, for now.

– As you wish, you are the boss. Those local smart guys, do they have any names?

– You shouldn’t know too much. Stasiek and Benek would suffice.

– Benek, Yid?

– A Jew – Andrzej corrected him. He hated that anti-Semitic slur.

– OK, OK. Your people, your job.

Andrzej briefed Edek and Julek. And then, in the evening, he met nearby with Stasiek and Benek. Casually, over a good mug of beer, they pratted like old friends, not like undercover agents working out the plan. But the plan it was.

Now all that was left, was to wait. Patiently. Very often police work is mostly waiting. The most important and the most difficult policeman’s task.

Wednesday, 13th May 1925

Edek and Julek turned up on Wednesday. A solid piece of scouting work complete.

– Chief inspector, – Edek started – we followed instructions. Here we have a list of people who last week left the boarding school premises. All written up, what they have done and where they have gone. That is, what they have done, until we handed the pursuit over to your local folks.

The list was not too long. Antek Poświatowski and Franek Kowalski from the pre-university course, Paweł Boruc from the Ninth Form, Wojtek Łyńka from the Eight Form. Those were regulars. There were some others, but those left the school only once. Antek was seen kissing a very attractive woman. Franek waited near Kobuszewski market[11] for a college girl, nothing special. Scouts handed over Paweł and Wojtek to Benek as soon as those got deeper into Bródno nooks. Neat job.

Andrzej checked some small details and asked them to keep watch.

Now he needed to talk with Stasiek and Benek.

They came to see him at his Ząbkowska apartment that very evening. He gave them money for the tram tickets and hosted with a rich dinner.

Thin like a willow, flaxen haired Stasiek, despite a heavily worn jacket, tried to keep up appearances, boasting a red scarf and a vile checked cap. However, the shoes, simply falling apart, gave away the true condition of his pocket. Andrzej spotted the size and recalled that he still had a good pair of Michał’s solid leather loafers, hand made by a pre-war cobbler, not today’s mass production. They should fit Stasiek. It would be a nice bonus for work properly done.

Benek, with his athletic posture was more impressive. He used to be a middle player with “Makabi”[12] . He dreamed of becoming a policeman, but they gave priority to ex-soldiers, and as a Jew, without patrons in the magistrature, he stood no chance of a state job. Anyway, he was the leader and prepared the brief.

Andrzej read the paper carefully.

– Thank you, chaps. Nice piece of detective work. Now I see the track leading clearly to the preparators. I still need to see them myself and better understand their plans.

– No offence old fella, but the roof’s pretty steep and slippery there, we can do all that detectin’.

– You don’t get it Benek. I need to be an eyewitness; the coppers will believe me. You told me that one can climb there from the backyard, correct?

– Yeah, but, mind you, no ladder . One has to be there early, ‘fore people come from the shift and wait. Very tiring.

– I’m not a gaffer yet, I will manage.

– Okay, as you wish sir. If you need us, we will come in a nick.

– Thanks for that. Tomorrow’s Thursday, the day. In the morning I will check the workshops, still need to find some more details. And then at nine at Siedzibna you said?

– Yeah.

Thursday 14th May, 1925

A. Kupniewski drawing, 1940 – workshops including round steam engines garage, empty spaces because of 1939 war destruction

The following morning Andrzej got out of “twenyone” and turned into cobbled Palestyńska street. At the small concierge hut they checked his pass carefully and let him in. He forked right immediately. The wooden management building was somehow hidden by green branches with rich young leaves, but he didn’t stop there and followed towards red-bricked factory halls, with large windows glimmering in the spring sun. That’s where the students attended practical classes and had a chance to earn some pocket money with turning or milling. He watched people lathing bronze boiler parts, repairing copper piping. He chatted with workers and foremen. Nothing. It was only in the last workshop, which boasted an impressive view of the famous round rail engine depot, where he met the old worker who told a curious story.

– Ye ken, guv, we thought that boys ‘r nicking. Mizgalski, our ol’ watch, checked pockets. And ye ken? Had good laugh. Shaving ‘ey ‘ve, the tiny ones. Copper and bronze shavings, mere dust. For chemical, experiments, ‘ey said.

– Whooo – the whistle rung like an alarm bell. The huge, heavy, black whale of the steam engine rolled out of the depot. The old man waited until the groaning, wheezing and din subdued and continued.

– Tomfoolery. We even broomed some stuff for ‘em.

– Do you recall which ones have carried those shavings?

– Who knows ‘em all? Surely, the tall ‘un, straw hair. Director’s pet. And the small ginger ‘un. Two, three more. Plenty.

Copper shavings. Interesting. He got outside and followed the Kiejstuta exit. The pieces were falling slowly into the right places.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ic3QqTrec0

At one o’clock he sat at the Popielarska’s[13] restaurant window and observed the Białołęcka street. In the back room some folks enjoyed billiards. The knocking of balls mixed with the phonograph playing “Wenn du meine Tante siehst”[14] the popularity of which bordered on obsession. The hit was catchy, it was difficult to keep feet from following the foxtrot movements. He sipped the beer slowly. It was just the proper one for the warm May day. Cold, with good head, bringing the refreshment one needs after the serious brainwork. If his sources were right, he should see her in a moment.

Precisely. She came. Stunning beauty as Benek said. Birch tall, she swam through the afternoon crowd. The real queen of the suburbs. How different from those local plump and busty blondes who worked the streets. A good six inches taller. Black hair cropped short, according to the latest houte couture demands. Small mauve toque paired with short, neatly fitting mantle, which in turn dragged eyes to her perfectly shaped calves. Four inch heels. How, wearing them, will she negotiate the muddy Oliwska street?

Andrzej threw a nickel[15] to the waiter and jumped to cut in her way. Shoved the girl lightly, caught her hand and then started to apologise. Sincerely, kissing her hands and pratting a lot of nonsense. It bought him time to admire her black eyes, so deep one could drown in them, tender lips, tiny dimple on the chin, and quite prominent cheek bones. Tatar’s blood. A real beauty, even if her “Shut ’up gaffer” was not on a very polite note. So that was the famous “Spear, the long one, that goes straight into your heart,” as Bródno’s men said.

So now he really knows “who”, it was just the last piece of the jigsaw to confirm “why”.

It was not that easy to get on the roof of the one storey wooden house at Siedzibna street. Fortunately, the fruit trees were in blossom and hid pretty well from the street gazers Andrzej climbing from the garden side . He got flat on the roof and lowered his invention towards the window beneath. It was not that easy to manoeuvre it inside. The rubber pipe with funnel ending was ideal for eavesdropping. It brought every sound straight to his ear. Then he waited. Minutes were passing slowly, taking hours. Watch hands moved at snail speed. In May the dusk comes only after nine. Six hours of patience. The air cooled down, dew stared to cover the roof, chimney, his face, dark clothes.

It was precisely quarter past nine. The blinking light of the street number lamp, attached as per regulation to each house, revealed Spear’s shape. One could not mistake her. With a man holding her tightly. Light hair. Tall Antek. Before getting inside, they stopped for a long, passionate kiss. A few minutes later – another short figure in the railway school uniform. And then, quite surprisingly, two broad shouldered adult males in long coats. Genuine Bródno criminals.

Doors clapped, stairs crackled under heavy steps. Then wheezing and grunting.

A harsh voice, coarse from drink, asked – You’ve got it?

– Tomorrow evening, boss. We need to shift the dust and put it into the sacks. – That was Antek.

– You’d better do. Else… – the man’s voice paused threateningly.

– No worries boss. – Spears’ deep voice joined the conversation. – Antek’s school uniform looks like real railwaymen, everyone trusts the conductor. He will guide the greedy fools to the youngster. Boy plays the soviet fugitive, selling family inheritance. He’s got that innocent look. People would buy it from the kid. They can’t resist quick profit. I will herd them. Lock, stock and barrel.

– Boss, you and Rusty better be on the watch. Else, someone may try to cut corners and get away with all the stash. It’s a good deal of money. – Antek added, trying to claim some authority.

Andrzej listened a few more minutes. He could not resist a smile. Old Warsaw trick. Almost forgotten after the war. Russian tradition. OK. He needed to move and get the cops.

He pulled the pipe slowly, inch by inch, shifting stiff muscles. And then Andrzej felt his wet clothes slipping on the roof. He pushed hands and legs apart, trying to slow down the movement. Franticallu he tried to grab for something to hold on. No chance. He will land in front of the doors. Antek will recognize him and they will just vanish like smoke in the wind. Damn, he really screwed up!

That was the last flash of his mind before he landed with a heavy thud. Twenty years ago, he would have jumped up, like a spring and be ready to fight or fly. Unfortunately, he had aged, his body would not listen anymore. The left arm, the one he damaged in 1890, twisted, he screamed in pain. Doors were pushed ajar. He felt something hard hitting his head and just passed out.

A stiff kick in the ribs brought him about. He lay in wet mud. His ankles and wrist were professionally bound, thin cord cut into his skin. His head was throbbing with pain.

– Alive, old goat? – The shape bending over him oozed with stale alcohol and onions dinner. – Enjoy, the last moments of your life. Hum, hum.

Where the hell am I? Red brick wall, piles of muddy earth, crosses. Sure. Bródno Cemetery. Fitting place to kick the bucket.

– Do you hear it? – The odour of yesterday’s vodka engulfed Andrzej again. – Rusty’s digging your grave.

Nice fella, isn’t he? – Andrzej thought – And what a stupid way to end life. In the past he had managed to avoid Azeri smugglers trap, skipped Jewish pimps knives, eluded English agents on spying mission in Nepal, survived weeks of Turkish artillery bombardment on the Great War front, came back safely from the land of Bolsheviks, only to be finished by a bunch of small crooks from Bródno. What a shame.

He tried to move, slowly, but the knots were done expertly. Not a chance. What could he do? He must not die now. He needed more time, more time to think. But his brain was still acting clumsy, his head throbbed. Had Anisa not forgotten to put the razor blade in his sleeve?

Anisa. The thought of wife came with a pricking pain. How would she manage in the strange land? Her Polish was still not the best. Michal would not give a damn about his foster father’s second wife. She would not survive on a meagre widow’s allowance.

Metal grinding the stone. Too late to do something. This time he allowed his pride to kill him. Benek or Stasiek could have done the job. Old stubborn goats, like him, deserved to be slaughtered.

Out of tune whistling “Wenn du meine Tante siehst”. Oh no, not that as a funeral march, just adding insult to injury. A tall shape with spade came from the background.

– Well, gaffer…

Swish. Scream. Loud plop of a body falling into muddy water.

– Beautiful night, chief inspector – Stasiek’s solemn voice sounded to him like an angel’s chorus.

Bright flashlight. Andrzej saw Stasiek hiding a famous street gang weapon – a lead ball affixed on a spring.

– You are a real meshugge[16] chief inspector. Enjoying a midnight stroll in the graveyard? – That was Benek. Sounding very pleased with himself, he cut the ropes and helped Andrzej get up. – How’s your head, chief?

– I will survive – Zaleski replied making an effort to hide dizziness and trying to forget the throbbing headache. He slowly stretched stiff muscles, brought circulation to his icy fingers. – Guys, you’ve just saved my life.

– We kept telling you chief inspector. T’was just our kinda’ work. We tried to keep an eye on you, but we had to wait until they brought you here and Rusty and Edek were alone. Otherwise we could have spoiled the trap.

They brought him to the very doors of the XXV Constabulary. He shook their hands and thanked them again. Shame such boys can’t join the police.

The young constable on the night duty was not impressed. He scrutinised Andrzej’s torn clothes and disheveled appearance.

– How can I help you? – The constable’s voice was definitely cold.

– I need to speak to chief inspector Rylski immediately. Please put me through. Tell him that major Zaleski needs him urgently.

Major, the rank always works. The constable connected him straight away.

– Hullo, Andrzej? Is that you, old mate? Have you popped in to enjoy a night cap together? – Despite the quite ungodly hour chief inspector Rylski voice sounded cheerful.

– Unfortunately, it’s business tonight. Can you, please, come to the watch house right now?

Ten minutes later the Chief Inspector Rylski listened attentively, stroking his curly grey hair and from time to time asking a pointed question.

– Unusual business, that’s true. The troupe is of course a bunch of Bródno’s usual suspects. The boss’s Black Julian, a real criminal. Racket, muggings, few bodies on his account. Spear, or rather Izabella, is his ex-mistress, or as some people maintain, his current one too. Rusty, known as Rusty Messer, is keen on knifing his opponents. Your schoolboys have chosen a nasty company. We must act at once; you never know how long they will survive. You said that the ingredients alone are worth almost six hundred and that they hoped to sell the stuff for at least three thousand? If so, Black Julian is not the one to share such spoils.

– Fine, let’s get to the job.

– Sorry Andrzej. We are the ones to do the job. That is what the State Police is for. You will go home and stay in bed. Cure your head. The horse cab is waiting.

He tried to dispute, but when he got up the dizziness took over and the young constable had to help him into the cab. Andrzej only begged Rylski not to reveal anything about his ordeal to Anisa. If she ever learned about the risk he took, of the near-death experience, she would go berserk.

At home Anise was clearly shaken, but somehow believed his story that included bruises, fall, but excluded the whole cemetery scene. She was cross, but uttered no word. Instead she took care of his arm, applied some poultice onto his head bump. She made him drink a vile concoction, bitter from willow bark, lemon sour and smelling of oriental herbs. Andrzej didn’t even recall ending up in bed.

Wednesday 15th May, 1925

He woke up close to ten. Drank a hearty bullion brought by Anise. The pain in his head and arm abated. He picked up the phone and dialed the number.

– I’d like to talk with attorney Adam Broch. Andrzej Zaleski speaking.

Hearing Andrzej’s name the young voice chipped in.

– Sir major, what a nice surprise! What can poor Adam do for his benefactor?

Adam might be joking, but he really owed Andrzej one. If not for Zaleski’s skills, Adam’s father would have ended up on gallows. Back in 1890, the famous Jewish attorney Leon Broch was accused of murders, and wouldn’t have been cleared without Andrzej’s detecting skills. Zaleski never used that link before, but now it was a proper time to ask for a small favour.

– Yeah, sure, interesting chap. – Adam Broch listened to Benek’s story. – Let me talk with councillor Saidenman, my dear Zionist friend. He’s a big fish in the Jewish council. Saidenman can be persuaded to bend some rules, for a worthwhile cause. That Benek of yours sounds exactly the type of brave and clever guy we need in our Jewish Watch.

– I thought so. – Andrzej happily tapped his moustache and smiled to Anisa. Maybe the Jewish Watch is not the State Police, but it’s a reputable institution. And pays the bills.

They chatted a few more minutes and agreed to meet for a dinner in “Simon and Stecki” restaurant, which recently brought a new chef and for the last thirty years consistently poured the best wines in Warsaw.

It was afternoon already, when Andrzej, arm wrapped securely under the shirt, wrists healing rapidly, came to the Michał’s office. His son did not even notice his father’s injuries.

– Can you tell me, what this was all about? – Michał was pacing impatiently.

– The old sting, one that comes from the Russian Empire’s time. They pretend to sell gold sand. Volume and weight right, in proper sacks, with bank seals. But in the sack, under a layer of gold, one finds a mix of bronze and copper dust. The sacks could be original, from the Russia Imperial Bank. Many have fallen foul of such treachery. To buy gold sand, half price. Times are hectic, people are afraid about the new złoty, of the return of inflation. They are looking for safe investment. Scoundrels spin a kind of story that brings tears to your eyes and sounds plausible. Young orphan, fugitive from the Soviets, sells what his parents left him, the remains of a family fortune. Nice Polish railway man helps him, just arranging, out of pity and good soul. People get attracted, easy prey, easy money. That is why boys were stealing gold, and money, to buy gold. They wanted pure gold for the upper layer. Had I known about those copper shavings at once, I could have resolved it myself.

– It is so hard to believe that Antek was the perpetrator. Such a good noble family. Real patriots. They kept sending him good money. I was ready to swear his innocence. – Michał grappled his fingers and rubbed hands nervously.

– Well, love is the answer. Antek’s fallen in love with beautiful Izabella, known as Spear, a real heart eater. She’s got him wrapped around her finger. First, she sucked all the money the family sent, and whatever he earned in the workshops. Her love is expensive. Do you know how much the mantle of hers is? Two hundred at least. When he was broke, she was ready to throw him away. Then he came up with the idea and found Wojtek Łyńko, a poor chap with quick fingers. Antek promised Wojtek a good share. “We will divide in three, there is a grand for you”. A thousand in cash, a fortune for a fifteen year old. They trained together and became quite skilled. Benek saw Wojtek nicking a wallet from a railway civil servant.

– What?! – Michał reddened with anger – He stole a wallet, in broad daylight, on a street?

– Not really. He put it back in the chap’s other pocket. He did it for fun, a childish prank. Wojtek has really nifty fingers. The plan was relatively simple. Gold. Money spent on gold, all turned to powder. Powdered copper shavings on the bottom. Love can be blind, but made Antek’s brain work hard.

– What will happen to the boys?

– I know chief inspector Rylski well. He will give the boys some chance to make up. Your fellows are frightened to death, they now work with the police. Helped to get back the gold and what’s left of money. The judge can be lenient. It can be a workhouse, not a real jail. A short sentence, for cooperation and repentance. Not serving among the worst criminals.

– I really pity Antek, such an able guy, wasted just because of the girl.

– I see it differently, Michał – Andrzej wasn’t ready to agree. – No one forced him to steal from his colleagues. A harsh lesson now, when he’s still young, can be beneficial. And his family is well off, they will forgive him and dig him out from that mire. At least Miss Janina will get her bracelet back. I saw it when I kissed Spear’s hand. Your Antek decided to carve out that personal gift for his lover. Wojtek, who’d actually done the job, was not even aware. However, it is Wojtek who deserves your pity. He will be left alone to deal with his criminal record. For such a kid from a poor family, the railway school was a true chance for a better life. With his able fingers, he could become a master mechanic. Now, without family or state help, he will end up somewhere in the slums.

– You are right, father. Neither the state nor family would help Wojtek. However, we can. It is worth investing a few hundreds in Wojtek’s future. – Michał reached for the phone receiver. – Miss Janina, please put me through to mister Śmiarowski. – He covered the mouthpiece and winked to his father, adding in stage whisper – You of course know attorney Śmiarowski? Not is not just the star of Warsaw’s bar association, but a highly regarded member of parliament. In Warsaw’s courts of law his word is the law. I work only with the best.

Andrzej stared at his son, not quite believing his eyes and ears.

Historical & Geographical note

Praga maintained a strong sense of identity, it’s own dialect (which survived until 70’s) and boasted significant Jewish population, amalgamated among other inhabitants. Praga’s citizens enjoyed an East Enders-like reputation.

The story is accompanied by additional explanatory endnotes. British Police Ranks have been used.

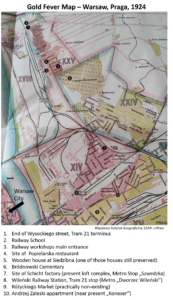

The curious reader will find to the right a Praga & Bródno Map from 1924 with places that are mentioned in the story marked.

Footnotes:

[1] Legions – the ex Austro-Hungarian Polish regiments commanded by Józef Piłsudski, they refused to swear allegiance to Germany at the end of 1916 and were largely interned. Haller’s army – Polish soldiers serving on Russian Empire side, who fled to newly formed Poland after the revolution, commanded by nationalist gen. Haller. Zaleski of course fought during the Great War on the Russian Empire side too. Red-green was the flag of Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party (Eser), who fought against Bolsheviks.

[2] Highest Polish military achievement decoration (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuti_Militari)

[3] ZLN – the Polish nationalist party, ruling in the right-wing government from 1923. They were Piłsudski’s political opponents.

[4] For the fiction purposes the school opening was brought forward from 1927 to 1924.

[5] Prior to World War I, Poland was partitioned between Russia, Germany and Austro-Hungarian Empires.

[6] The monetary reform in 1924 replaced the Polish Mark with a new currency Złoty. It also increased taxes and brought budgetary balance with big spending cuts.

[7] Modern-day equivalent of £5000.

[8] Schicht cosmetic factory was opened in Praga on Szwedzka street in 1921

[9] (latin) Operating mode

[10] (latin) Opportunity makes a chief

[11] Local interwar market, run by Edward Kobuszewski – the famous Polish actor’s father.

[12] Makabi – leading Jewish sport club in interwar Warsaw

[13] Real restaurant with billiard pool in the interwar Bródno

[14] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5jmhiVYWnuo the Polish version adapted by the local cabaret, become an instant hit in interwar Warsaw

[15] Here used as a coin. A beer in pre-war Warsaw was approx. 30 groszy. One złoty equals 100 groszy.

[16] Crazy in Yiddish